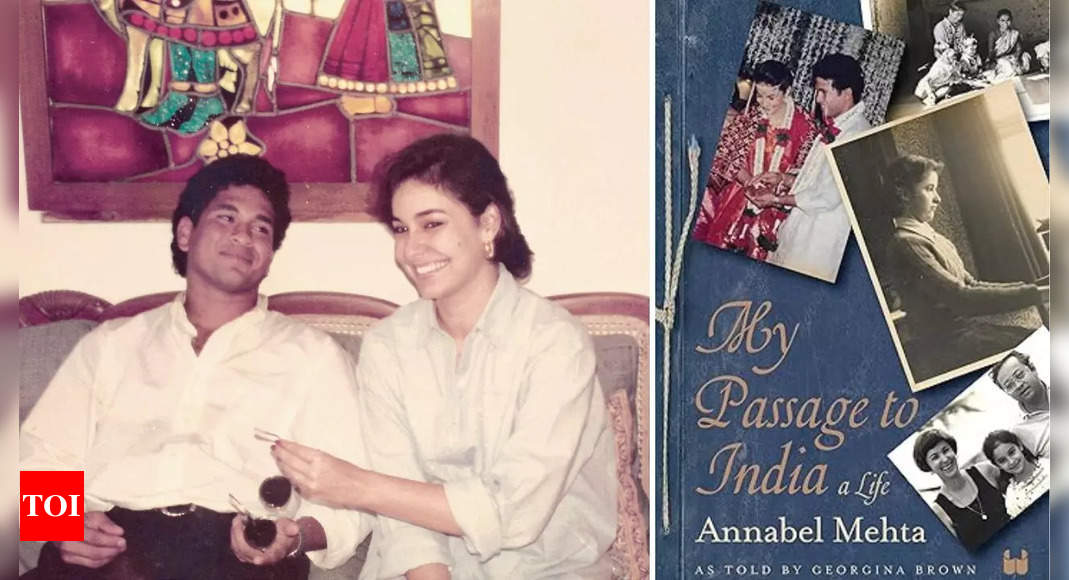

Revealing her own extra-ordinary journey from England to India in the 1950s for love and some lesser-known details about Sachin and Anjali, Sachin Tendulkar’s mother-in-law and Anjali Tendulkar‘s mother– Annabel Mehta has now written an effortlessly engaging memoir titled ‘My Passage to India‘.For the unversed, Annabel Mehta is the Founder of Apnalaya– a non-profit organisation that works for underprivileged children in Mumbai, India.

Here’s an exclusive excerpt from the book ‘My Passage to India: A Memoir’ written by Annabel Mehta and Georgina Brown, published by Westland Books.

Chapter 6: When Anjali Met Sachin

Sachin and Anjali Tendulkar with Anjali’s parents

Anjali, Sachin and Muffi were waiting for me at my brother Richard’s house in Bayswater. I asked them to leave me with Sachin. As we sat down on benches either side of the long kitchen table, I thought how young and sweet he looked, and I had to remind myself why we were there. I told him that Anjali was our very precious only child, doubly precious because we had lost our second daughter, and I asked him what his intentions were as far as Anjali was concerned. Traditionally, in England, this would have been the father’s remit. However, Anand is nothing like a traditional British male, which is one of the reasons I married him. He loathes confrontations. Moreover, he could have won Mastermind on the subject of the nineteen-year-old Master Blaster’s career thus far, so he might not have been terribly objective about Sachin’s suitability as his daughter’s intended.

I had clocked by then that Sachin was the brightest star in the Indian cricketing firmament, but I was concerned by the possibility of him becoming a playboy like so many of his fellow cricketers. It comes with the territory. Sachin in India in the nineties was like David Beckham in England. I needed to look him in the eye and ask him how he felt about my daughter.

‘We want to get married’ were his precise words, sweeping the rug from beneath my feet. I was astounded. I had always imagined Anjali marrying a tall, dark and handsome man. Dark and handsome, Sachin was. But at nineteen, he was still a boy. And so small. Barely taller than Anjali, who is five-foot-five and a half. Sachin’s bouncy hair possibly gives him another inch, but not enough for Anjali to wear the high heels she had always loved.

Anjali told me later that Sachin had made it clear from their first date that he was serious. She was his first girlfriend and he was convinced that she was The One. They were truly, madly, deeply in love; I could see that. And all I wanted was for Anjali to be happy. At a later stage, I would worry that he was away for long periods of time, which would test them in all sorts of ways, but all I could see at that moment was his young, innocent, hopeful, ecstatic face.

They had sensibly decided against running away to Gretna Green, which they had considered for a while. In India, men are not legally allowed to marry until they are twenty-one (a law flagrantly ignored); he was only nineteen, and Anjali was yet to complete her postgraduate medical degree. They would have to wait another two years and then they would marry in Mumbai. In the meantime, I told him, we would be happy to keep their secret.

Sachin and Anjali Tendulkar and their kids with Anjali’s parents

At one level, life continued as normal. I continued to work with my charity, Apnalaya, and told no one about Sachin, though he became a frequent visitor to our house on Warden Road. Not that everyone recognised him. My sister-in-law Tulsi once mistook him for the son of our Gurkha watchman. But the man who sold chana on the street, as well as the security people at the American Consulate across the road, would definitely have known his face, and yet none of them ever tipped off the press. I can only surmise that they felt it would have been the betrayal of a superhero. I find that very touching.

So it went on, with Sachin totally taken up with cricket and Anjali with her paediatrics, living in the hostel at JJ Hospital. But she was obviously getting impatient, and one evening, when Sachin rang from New Zealand, she asked him when he planned to propose. After a short pause for thought, he instructed her matter-of-factly to go and ask his parents for their permission to get married. Sachin, a respectful son, would not get engaged without his parents’ consent. If they agreed, the engagement could be held as soon as he returned home, provided of course that Anand and I also approved. We had no hesitation.

It was all rather unconventional, to say the least. Sachin’s elder brother, Ajit, arranged the meeting between Anjali and his parents. We didn’t meet Sachin’s parents until shortly before the engagement. Despite coming from different social circles, we got on splendidly. They were solid, middle-class Maharashtrians and devout Hindus. As is Sachin. His father, Ramesh, was an acclaimed poet as well as a professor of Marathi Literature at Kirti College. His mother, Rajni, worked for the Life Insurance Corporation. Sachin’s mother has only ever spoken her mother tongue, but his father spoke English.

The engagement took place on Sachin’s twenty-first birthday, 24 April 1994, at our house, with a lunch for twenty-five relations, followed by a formal announcement to the press. When Sachin had been away in Dubai, he had instructed Anjali and me to go and see our jeweller friend Sanjeev for Anjali to choose a ring. Sanjeev let her take home a simple, small diamond ring, which she judged appropriate for a medical student working in a government hospital, for Sachin to approve when he came back. There is a lovely photograph of Sachin putting the ring on her finger and kissing her, which he has never permitted to be shown to the public. He is a very private person.

Needless to say, the press went wild. Nobody had a clue who this Anjali Mehta was. The only picture they could find was a mugshot taken when she enrolled at St Xavier’s College at the age of sixteen, rather different from the beautiful young woman she had become. Following the announcement that Sachin was now spoken for, it was reported that millions of Indian girls went into mourning. The fact that Sachin was only twenty-one and hadn’t played the field romantically attracted considerable attention. As did Anjali, especially as she was nearly five years older.

I count my blessings that I became the mother-in-law of someone everyone loves and who has lived a blameless life and become a role model to so many. At nineteen, Sachin was a sweet, shy, soft-spoken boy of few words. When I commented to Anjali about how quiet he was, she said: ‘You should meet the rest of his family; they’re completely silent!’ Like Anand and me, they both recognised how different their backgrounds were and neither underestimated how much it mattered.

Excerpted with permission from ‘My Passage to India: A Memoir’, written by Annabel Mehta and Georgina Brown, published by Westland Books.

Shah Rukh, Sachin Touch Amitabh Bachchan’s Feet At Ambani Wedding | Watch